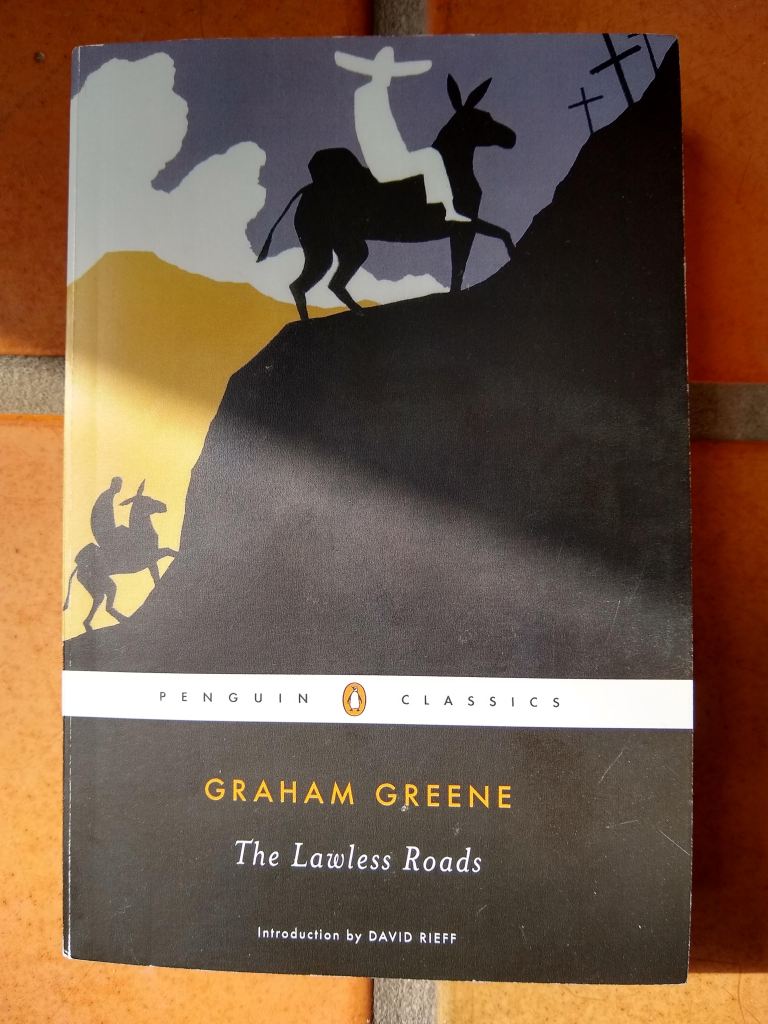

The Lawless Roads

Published 1939

Graham Greene does not seem to enjoy travelling. He never stops complaining about the people he meets, how uncomfortable he is and how ugly or monotonous many of the places he visits are. Then again, judging from the sourness present in almost all of his books, he may feel the same about England. Yet, with distance and an uncomfortable bed and rats crawling over him, his house in England seems a distant Paradise that he inexplicably forsook. He spends uncomfortable nights under a mosquito net reading a novel by Anthony Trollope with morose homesickness. A desperate situation indeed. Anthony Trollope wrote some of the most boring novels that I have ever read.

Perhaps his whininess is a bit of a pose. Or perhaps Greene is an idiot when it comes to travelling. Either way, he chooses very rugged travel routes with little planning ahead of time and he accepts travel methods that guarantee that he will be miserable. According to a back-cover blurber, this book and Journey without Maps “reveal Greene’s ravening spiritual hunger”. So, perhaps he approaches travel as form of penance. Expiation for the sinful comforts of home.

He went to Mexico with a commission to write on the situation of the Catholic church there. While the anti-clerical laws put in place by President Calles were not in force any longer nationwide, the Church had lost most of its property and the number of priests throughout the country remained minimal. In some states, Catholicism was still illegal. As he explains in a note at the beginning of the book, this commission explains why he carefully explains the religious situation in each town he visits and skips a broader discussion of Mexican culture. This raison d’être for the book will be its downfall.

Greene crossed into Mexico from the United States at Laredo. He made his way by train to Mexico City, with brief stops in Monterey and San Luis Potosí. But his primary goal were Tabasco and the mountains of Chiapas. After descending from Mexico City to Veracruz by train, Greene took a death-wish ferry to Frontera, a small port in Tabasco. Proceeding by riverboat to Villahermosa, the capital of Tabasco, and then by airplane into Chiapas. Within Chiapas, he traveled by airplane, mule or bus. He finally flew back to Mexico City from Tuxtla, the capital of Chiapas, with a stop in Oaxaca.

Viewing his travels through the lens of Catholicism, its expression and suppression, wherever he goes he tries to make contact with people important to the cause of the Church. He wangles an interview with General Saturnino Cedillo, the warlord of San Luis Potosí. Cedillo had allowed the Church to operate openly, saying he bowed to the wishes of his people. The General is the type of character that Greene appreciates, colorful, flawed, in charge, with an ad hoc approach to governance free from ideology. Of course, the General was doing a poor job and few regretted it when the Mexican government removed him from power several weeks later.

In Mexico city he meets with lay members of the Church and a priest who are part of a Catholic Action group, trying to preserve the Church’s social functions despite the suppression and on-going economic and personnel difficulties faced by the Church. He visits an underground school, training working-class men and women in trades. Shortly before he leaves Mexico City to return to Europe, he even attends a stuffy party celebrating the jubilee (50th anniversary of ordination) for an archbishop.

Greene seems dutifully respectful for the church’s representatives in Mexico City and the other cities he visits. However, his writing about Catholics throughout the cities he visits is simply reporting. He has a greater interest in the spirituality of the indigenous people he sees in Chiapas, whose methods of worship he describes in rapt detail. Greene perceives a deeper basis for their spirituality. His description of this is perhaps the only part of the book that is personal without being sarcastic or bitter.

I cannot help but think that there is some sense of urgency regarding the persecution of Catholicism in Mexico that I am lacking that makes it difficult for me to understand what the big deal is. When the Church has power it oppresses, when the gyre swings the other way, the Church is oppressed. Violent and pointless? Certainly. What did the Church have to offer? The education and social solidarity of Catholic Action? Secular education and other social groups can provide that. Spiritual significance? The indigenous people Greene encountered in Chiapas were able to find that even with the priests gone.

Greene had several experiences that were well worth capturing: meeting Cedillo, the nightlife of Mexico City, the journeys from Mexico City to Tabasco and through Tabasco and Chiapas. Several of the people he met along the way and befriended made for interesting accounts. His journeys by mule were also prime material. These experiences, fleshed out, could have formed an excellent travel narrative. As it is, the focus on the Church makes much of this book irrelevant and dull.