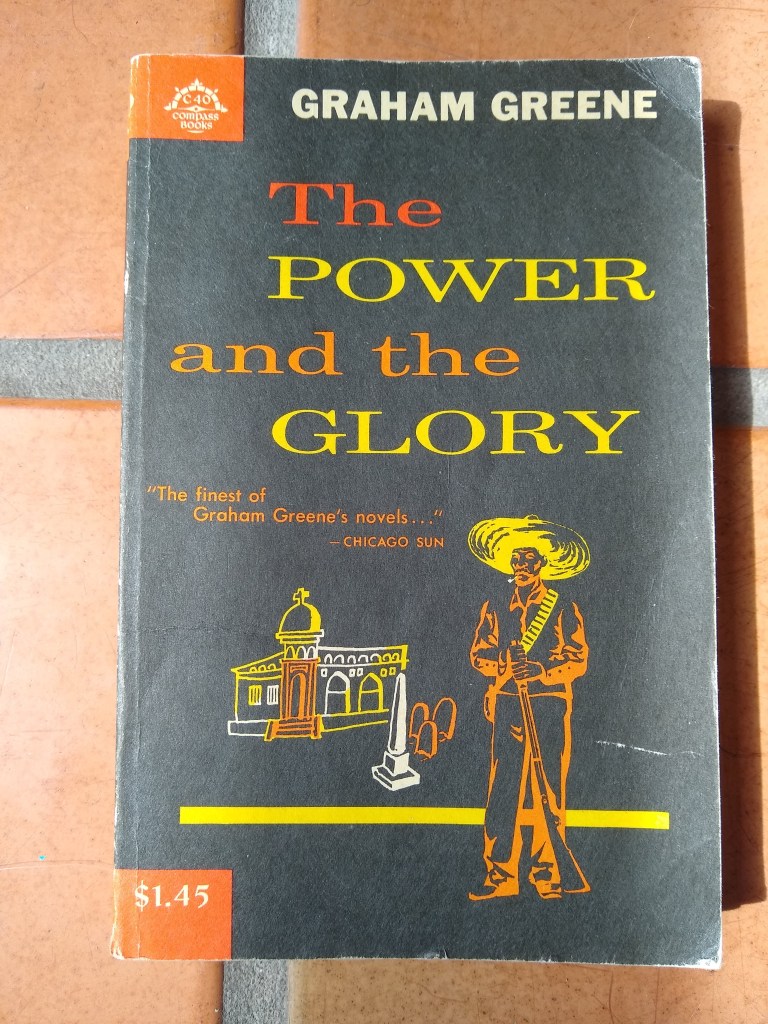

The Power and the Glory

Also called “The Labyrinthine Ways”

Published 1940

Perhaps it’s because I’ve only been reading Graham Greene novels this year, but every one of his books seems like it has been carefully contrived by the man Graham Greene. This latter designs characters to elicit so much sympathy and interest on the reader’s part, before displaying just how ugly and unlovable they really are. In the end, we are left with a strong sense of how pointless life is and how good, evil, and banality are so mixed together in the world that any attempt to separate them would destroy the world. His books raise all possibilities for redemption (spiritual or mundane) and knock them down one by one. Yet, since Greene keeps returning to this theme of right action in difficult circumstances and did not kill himself, I can’t help but think that this repeated despair is a narrative posture that represents the era he was writing in or the restless unhappiness of a man at the end of his youth or perhaps it simply sold books.

*

Guilt is only possible to one with a sense of right and wrong. The priest in this book is guilty due to his strong sense of his own immorality. He has been hiding from the authorities for eight years, after the church has been banned and anyone practicing Catholicism liable to punishment. Priests could avoid prison or death by marrying, but the priest in this book did not follow that path. He took to the woods and has been saying mass, hearing confessions and performing baptisms as much as he dares.

However, the priest is a drunk, a “whiskey priest” as villagers call his type. And he has a child, the result of loneliness and brandy. I have no problem with a priest with a child, but, as he recognizes, it’s terrible to abandon her to her fate, going around and calling strange people, “My child” (as priests used to do). Throughout his trials, he grows aware of how the pride of the young priest, the center of attention in his parish, has morphed into the pride of being the only practicing priest in the state, the pride of a man who does his duty. But pride is a sin. Over the past eight years the world has presented opportunities for him to do good, yet his exile, this extended Passion, have not turned his heart into gold. He is still a sinner and the duties he holds to help no one.

An ambitious young lieutenant has begun a relentless policy in order to ensnare the priest. He will take hostages from every village and if the priest visits the village and the villagers do not report it, he will kill the village’s hostage. Soon, the priest finds that he cannot stay in any village and finally decides to leave the state. But duty calls him back across the border almost immediately.

Across the book, it becomes clear that the lieutenant is the better man. He is more moral and clear-eyed. Even the priest recognizes this. The lieutenant can be brutal. He can damn a person in this life. But the priest is even more brutal as he believes in the possibility of eternal damnation. He performs his duties to help others avoid future damnation, whereas the lieutenant performs his duties to help others in real life. I’m with the lieutenant. Should the priest be shot? No, a priest such as this should be plied with drink and serve as an example. That would have been a more fitting damnation.

But, to weigh on the side of banality, the book ends with the triumph of religion as fiction. If this sinful priest, the unwilling martyr, can become the hero saint for the credulous, then religion need be no more than a pack of lies.