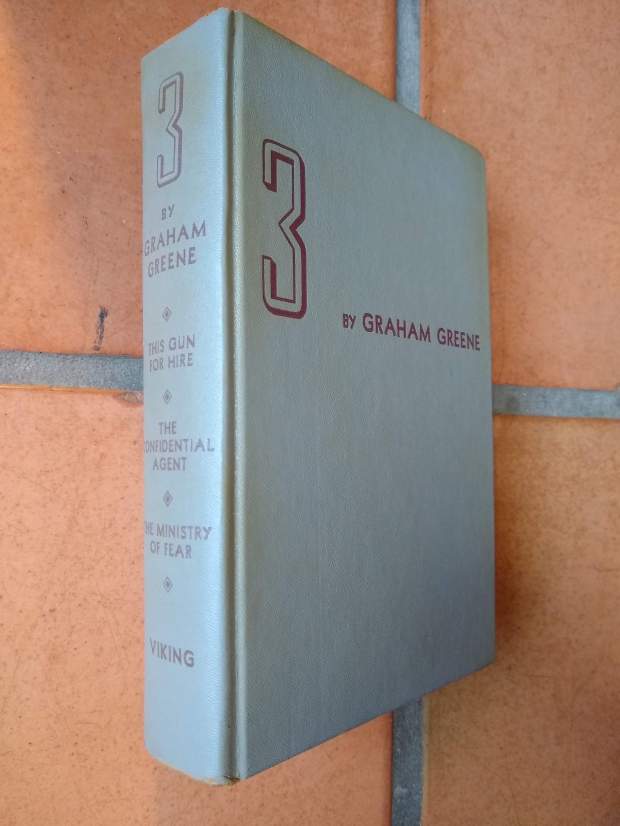

The Ministry of Fear

Published in 1943

Written during WWII, the nightly experience of the Blitz forms part of the background of this strange, Kafka-esque novel. The outcome of the War was still undecided when this book was written and so the espionage that drives the plot was of vibrant concern. Fear of spies, fear of losing and the consequences that would bring, and the not theoretical fear of dying in the night when the Luftwaffe rained munitions on London were shaping the psyche of the inhabitants of that city. This book contains a barely believable, at times comic plot, but explores deeper themes about what kind of people could come out of the War, even if they won.

Picture Arthur Rowe, a melancholy middle-aged man who spent time in jail for murdering his wife. He avoided the gallows and a longer sentence because it was a mercy killing: poisoned milk for his wife who was suffering from terminal and very painful cancer. The judge felt compassion for his difficult situation, as did the newspapers, which had covered the trial in detail. But Rowe has never forgiven himself and carries his guilt with him always.

To break the monotony of the week, Rowe goes to a small street fair. He plays some of the games of chance, he buys a book at the rummage sale, he wins a cake because of a hint that the fortune teller at the fair gives him. He counts himself lucky since the cake is the first made with eggs that he has had since the war began. But the street fair organizers demand the cake back and they’re willing to blackmail, frame, or kill Rowe to get it back.

These ersatz street fair organizers fail to eliminate Rowe. As he tries to determine what is going on, he meets Anna and Willi Hilfe, two Austrian siblings who work for the organization that put on the fair. Willi helps Rowe with great enthusiasm. Anna is more demure and tries to warn Rowe to get away from her brother, but does not provide any specifics. Anna’s help doesn’t prevent Rowe from being framed for (apparent) murder or from being tricked into carrying a bomb into an apartment building. The bomb, however, doesn’t kill him.

Rowe wakes up in a sanitarium without any memory beyond his youth. He cannot remembers his marriage or his wife’s death. He cannot remember the Hitler or the Blitz. Although he cannot make the comparison, he is happier than he has been for decades. The rest of the book revolves around him remembering enough of his life to help thwart the spies, while not remembering so much that he loses his happiness.

In addition to Kafka’s The Trial, this work reminds me of Anouilh’s Le voyageur sans bagage, a play about a veteran of WWI who has lost his memory but whose family have traced him and want him returned to them. In their presence, the amnesiac remembers them and his youth. He remembers also how horrible a person he was in his family and decides that it is better not to remember, and to start a new life. Rowe’s loss of memory similarly allows for a happiness not possible with a whole life-story. As Greene puts it, “He didn’t understand suffering because he had forgotten that he had ever suffered.” For the book’s readers, life during WWII and, specifically, the Blitz provided a great store of memories that anyone could have been happier without.

In the end, Anna and Rowe move into the future together with a past that they must not remember.