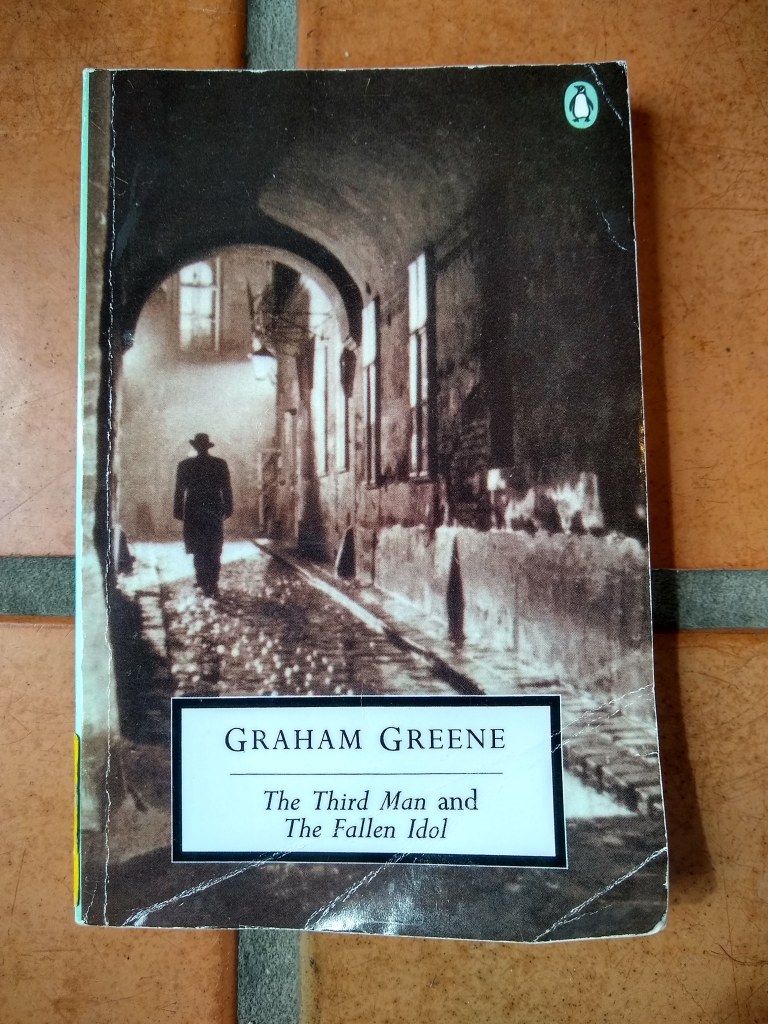

The Third Man

Published 1949

When writer of dime-store westerns Rollo Martins arrives in Ally-occupied Vienna at the request of his old school friend, Harry Lime, he is surprised Harry doesn’t meet him at the airport. He makes his way to Harry’s apartment only to find that he just missed him, but if he hurries to the graveyard, he may be able to catch his funeral. Few people are at the funeral, and only a single person looks sad, a beautiful young woman who clearly was Harry’s girl. Also at the funeral is a police officer who is happy to give Rollo a ride and very eager to ask some questions about Harry.

Everyone in occupied Vienna is involved in a racket, but Harry was involved in a very nasty one. He sold adulterated penicillin to hospitals, leading to the deaths of many children. This was known, but the police hadn’t had enough proof to arrest him until now, and then Harry was run over by a delivery van. Rollo doesn’t want to believe that Harry was involved in such a nasty racket, but as he has little reason anymore to be in Vienna, he starts visiting Harry’s friends and asking questions. He discovers that Harry wasn’t the person he thought he was and that something is not right about the way he died.

[Go watch the movie to find out what happens.]

This book exudes mood. A great city at peace, but still in ruins. The future shrinks against the impossibilities of today. The city is divided into American, British, French and Soviet zones. But the Cold War is beginning and people occasionally disappear in the Soviet zone.

In this place between, this time between a brutal past and a future that may not be any different, does human life have any value? When you look at others from a distance, little black dots moving around like ants, does it really matter if one or a few of those black dots stopped moving? Would you care if some of those dots stopped moving if you made a lot of money? Harry Lime wasn’t the only person who answered these questions, “No.” Like any functioning psychopath, Harry doesn’t have ill will toward others, he just doesn’t feel any compunction if his actions kill them.

*

As Greene explains in the introduction, this novella was written as a film treatment. Thus, this book reads like a movie, it has almost no description of the thoughts of characters and the plot plays out in scenes for which we can imagine the exact camera shot, the close-ups, the panoramas, the fade-outs. Greene’s writing had a reputation for being cinematic, but he ratchets up the cinematography in this story to a new high. This book is written in 24 frames per second.