My Year in Greeneland

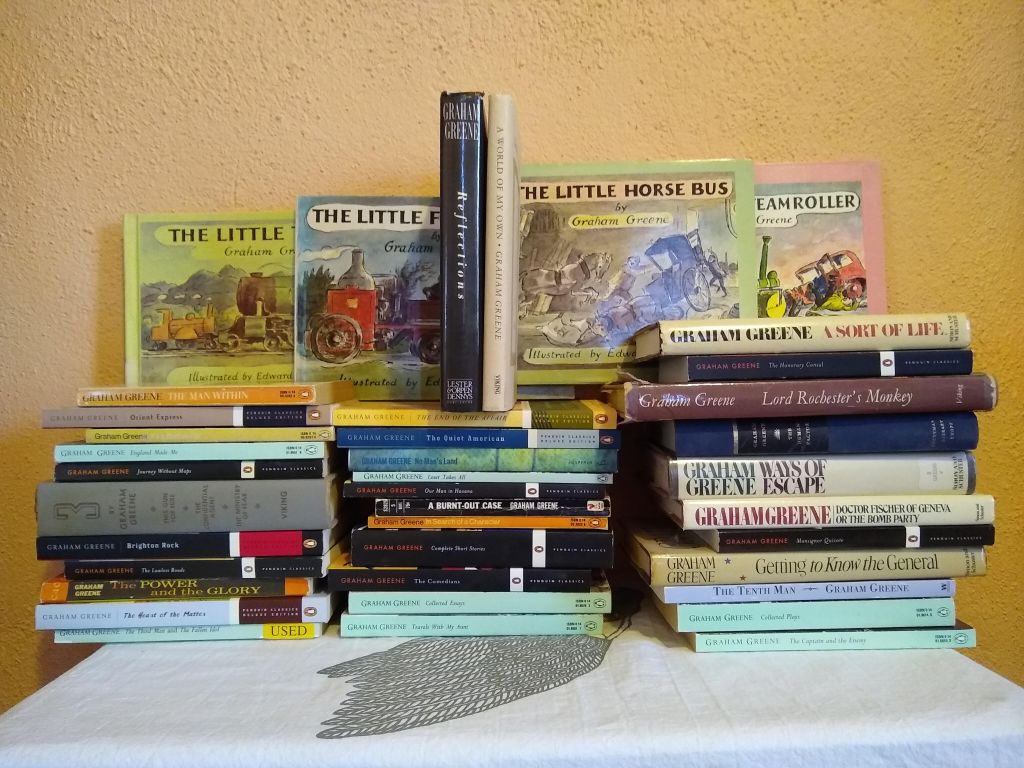

I have finished reading all the works of Graham Greene that I set out to at the beginning of this year. I have read all his novels, short stories, and plays, as well as the essays that he collected and published during his lifetime. In this brief retrospective, I will discuss my experiences in Greeneland and the souvenirs I brought back.

*

Having never read an author from youth to the grave in this manner, I have generally judged an author by their books as if they were a static person of unchanging ability. One book might be better than another, but it was all part of the Gestalt of the author. That is nonsense, of course. Reading Greene’s books in rough chronological order, especially since he was a prolific author with a sixty-year career, has forced me to consider each of his books within the context of each period of his life. Over time, he developed his skill as a writer and, as someone deeply interested in the world around him, the topics he wrote about often reflect the time in which he wrote the book.

His first three books (The Man Within, The Name of Action, and Rumour at Nightfall) are unusual in that they stand out of time or, to put it another way, they are not realistic novels and the eras in which they are set do not impinge upon the story (even though Rumour at Nightfall is historic fiction). None of these novels are particularly interesting and I understand why Greene repudiated two of them. His remaining novels of the 1930s (Stamboul Train, It’s a Battlefield, England Made Me, A Gun for Sale, Brighton Rock, and The Confidential Agent) provide an excellent overview of a sooty and violent 1930s, both in England and other parts of Europe. Of these books, Brighton Rock is, without a doubt, the best. It’s a Battlefield is a book that I liked without knowing why. At this stage in his career, Greene still made a distinction between novels and “entertainments”, books that he didn’t consider as serious. A Gun for Sale and The Confidential Agent are examples of the latter. They are fun reads.

I felt his two travel books of the 1930s, Journey without Maps and The Lawless Roads, were dull. He certainly had unusual experiences in Liberia and Mexico, but his descriptions of both places dwelt so much on his discomfort that I found them annoying. However, he drew great inspiration from his experience in both places in his later fiction.

Greene’s early books are all very emotionally raw, with the agony of life square within the sights of the reader throughout the book. At times, reading them felt to me like someone staring at me with a grimace as they slowly ripped off one scab after another. The agonic theme remains in his novels from the 40s (The Power and the Glory, The Ministry of Truth, The Heart of the Matter, The Third Man, and The End of the Affair), but, perhaps because of his greater maturity and economic security, the edge of the agony is not as sharp and he explores how the way we approach our personal hells determines the depth of their abysses.

Many consider The Power and the Glory to be one of Greene’s greatest novels. Yet, more often than not, I found myself agreeing with the Lieutenant, the antagonist of the book, which either testifies to Greene’s writing ability or to my own perversity. It is a difficult book. One which I will read again as I do not think that I appreciated it well enough the first time. The Ministry of Fear was another of Greene’s entertainments, although it’s not as interesting as the first two. The End of the Affair was published in 1951 but has more in common thematically with his earlier works than with his later works. I did not like this novel. It contains a harrowing description of London during the Blitz and is skillfully written, but the characters are all uninteresting to me and the story is at first dull then unbelievable. It’s with the The Heart of the Matter, from 1948, that Greene begins to show his full ability: complex characters who are tricking themselves, moral ambiguities that resolve themselves into absurdities, tight descriptions of real places given the Greene treatment and thus turned into part of Greeneland.

Almost all of Greene’s novels in the 50s and 60s were excellent. The Quiet American, Our Man in Havana, A Burnt-Out Case, The Comedians, Travels with My Aunt: These are peak Graham Greene. The seediness is still there. So is characters’ dubious intention and actions’ uncertain effect. So is the possibility of the soul’s damnation and the body’s torture. All these things are still there. But: humor has crept into the books. In fact, humor underlies the plot and humor is the medium for the most tragic elements of each book. When the world is absurd, drama is a distraction and humor can cut to the chase. These books all draw copiously from his travels and journalism. They share a verisimilitude into which the novel’s plot is slipped as if it’s just one story among many.

After this, Greene published two more novels in this mold: The Honorary Consul and The Human Factor. The first making further use of his travels in Argentina and Paraguay and the second making use of his time in English intelligence, but also drawing from the experience of Kim Philby. His final three novels have a slower pace and are more introspective: Doctor Fischer of Geneva or the Bomb Party, Monsignor Quixote, and The Captain and the Enemy. These are all good books, and each introduces one or two characters with unconventional behavior that we come to understand and, perhaps, to sympathize with.

Greene’s short stories were a surprise to me as Greene is known for his novels and so I had no expectations when I began reading his shorter fiction. They are, overall, excellent and not to be missed. Get a cheap copy of his Complete Short Stories, which includes Twenty One Stories, A Sense of Reality, May We Borrow Your Husband?, and The Last Word and Other Stories as well as four uncollected stories. Some of these stories are spectacular and among his best writing. He explores themes and genres that he didn’t touch in his novels, such as slapstick comedy and fantasy. A Sense of Reality has a couple of longer short stories in this latter genre that are among his best. The medium of a short story allowed him to explore ideas that would have been too risky to try to construct a novel around. (Writing a novel is a great commitment: if a short story doesn’t work out, it’s not so great a loss.)

While his short stories were a happy surprise, his plays were a drag to read through. I was not entirely surprised, because the discussion of his midlife foray into theater that he included in Ways of Escape made me anticipate that they were not successful, artistically or critically.

Greene wrote several other books of nonfiction. His third book of travel (or autobiography as it’s often labeled), Getting to Know the General, recounts his experience in Panama and Nicaragua with Omar Torrijos and José de Jesús Martínez. He held a deep affection for Torrijos and Martínez and was happy to be used by them to support Central American causes. His experience in Panama informs The Captain and the Enemy and one of his later short stories. Greene wrote two other autobiographies, A Sort of Life and Ways of Escape, the former covers his childhood and youth, and is dull, the latter covers his literary career, and is quite interesting if you have read his novels. Lord Rochester’s Monkey was well written and informative and the most unlike any of Greene’s other books.

*

Over such a long career, Greene covered many topics and pursued many themes. One theme that appears throughout his fiction is the difficulty doing the right thing. If our intentions are pure, we may still be misinformed; if our intentions are mercenary, we may still effect good. Even after we have acted, we may not understand the significance of our action. How can we be good when we cannot understand if the results of our actions are good? Also, as many of Greene’s books have testified, all of life is incidental. One thing happens after another and how we react to these incidents and, more importantly, how we react to the people around us is the only thing that matters. Indeed, it is the only thing that can matter. In this sense, Greene is a humanist, albeit one with a dim view of most human institutions.

Greene was an aficionado of the cinema and wrote movie reviews for much of the 30s. He wrote some of his early fiction with the idea of it becoming a movie in mind. In fact, the scenes in some of his books read like movie shots (e.g., the end of The Confidential Agent), and I imagine he had specific cinematic effects in mind when he wrote them. I suspect that one other influence of the cinematic vision within his novels is the rarity of a narrator intruding into the story. Instead, he builds up scenes in which the characters’ dialogue moves the plot along. In this way, Greene’s books are very different from the literary influences that Greene cites from the generation before, including Henry James and Joseph Conrad.

My Favorite Book

My favorite Graham Greene book is The Quiet American. The conflict in Indo-China was something that Greene covered extensively as a journalist and his knowledge of the subject flows through this book in its angriest, most absurd passages. The choice of the journalist-protagonist in this novel whether to become engagé, even if not for entirely pure reasons, is a choice that Greene wrestled with. The book is even more remarkable when one considers that it was written before the American war in Vietnam began. The futility of Western intervention was already apparent to Greene, who portrays the diversity of societies in Vietnam, each with its own goals. After reading this book, I recommend reading his journalistic writing of Indo-China, much of which is gathered in Reflections.

Overall, I found his later novels to be more consistently better than his earlier novels. I think this is due both to his increasing skill as a writer as well as his financial and professional ability after WWII to travel more, thus providing more interesting material for him to incorporate in his fiction.

What I Didn’t Read

The main genre of Greene that I didn’t read was his movie reviews. I am not particularly interested in the cinema and found the idea of reading reviews for movies I had never seen boring. I also only read those pieces of his journalism that he included in Ways of Escape and Reflections. Those were well worth reading. If I were to search out more Greene to read, it would be his journalism. Beyond that, he wrote a biography of a lady who was a neighbor of his in Capri that I chose not to read. (It’s supposed to be made up largely of excerpts from her diary.) Finally, many of his letters have been published in Graham Greene: A Life in Letters by Richard Greene (who is amusingly unrelated to Graham). It’s supposed to be well-written, but I wanted to stick with (Graham) Greene’s published works. I also briefly considered trying to cram Norman Sherry’s three volume The Life of Graham Greene into this reading project, but the thought of adding close to 2,500 pages of a biography known to be thorough to the point of tedium was more than I could bear.

Would I do this again?

I’m not sure I would. I have enjoyed Greene’s works, but reading them has pushed reading other fiction out of the picture. I look forward to reading more eclectically in the new year. But if I did want to try a project like this again, as an even bigger challenge I would read all the works of Henry James in a year.

—

Thank you for reading and farewell!